How Did the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act Facilitate Bank Consolidation?

Today, a financial manager can call a single bank to manage loans, securities, and cash for the business they represent. Prior to 1999, however, this level of comprehensive service was not just unheard-of, but illegal.

The shift from separate investment and cash management companies to a one-stop shop began in the 1970s. About twenty years later, growing desire for this consolidated solution drove the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act [GLBA].

Banking Under the Glass-Steagall Act

To understand the significant changes made by the GLBA, it is first important to understand the prior laws that governed the banking industry. The most significant of these was a holdover from the Great Depression called the Glass-Steagall Act.

During the Great Depression, approximately 9,000 banks failed, and policymakers at the time concluded that the interconnectedness of commercial and investment banking was a primary driver. In response, lawmakers passed the Glass-Steagall Act which created a legal barrier between the two functions.

Under the Glass-Steagall Act, commercial banks could accept deposits and issue loans, but they could not underwrite or deal in securities. On the other hand, investment banks could underwrite and trade in securities, but they were prohibited from accepting traditional deposits.

This barrier endured for decades, and banks were somewhat comfortably separated until a rise in technology and financial needs in the 1970s and 1980s. Changing consumer demands during this time paved the way for the GLBA.

Banks Sought Expansion Opportunities and Loopholes

In the 1970s and 80s, technological advancements spurred a spirit of interconnectedness that spanned trade, business, and banking. During this period, consumers began demanding more sophisticated financial products and seeking a consolidated financial service to meet their changing needs.

Many banks were eager to provide a one-stop shop for customers, but the law prevented them from doing so. Consequently, they began finding loopholes in the regulations.

The “Engaged Principally” Loophole

The wording of the Glass-Steagall Act prohibited commercial banks from affiliating with firms that were “engaged principally” in underwriting and dealing securities. This wording was challenged, and the Federal Reserve interpreted this phrase to mean that a relationship was legal if the subsidiary’s securities dealings were a small percentage of total revenue.

The relationships allowed under this loophole were known as Section 20 subsidiaries, and they allowed bank holding companies to engage in some investment banking activities. By the year 2000, there were 51 of these subsidiaries operating across the nation.

State Charter and Small-Town Insurance Loopholes

Along with investment banking activities, commercial banks were generally prohibited from selling insurance. They found two common “side routes” to bypass this legal barrier – a small-town exception and a state charter.

The “Small Town” loophole relied on a specific provision from the Comptroller of the Currency which allowed national banks to sell insurance in offices located in towns with populations under 5,000. Additionally, some states passed laws allowing state-chartered banks to sell insurance products.

The loopholes and patchwork of state insurance regulations made the banking system inefficient and confusing. In turn, banks and consumers advocated for legal reform that simplified the regulations and allowed for an all-in-one solution.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999

Tensions reached a tipping point in 1993 when Citigroup, a commercial bank, and Travelers Group, an insurance and investment giant, proposed a merger. This consolidation was not allowed by the Glass-Steagall Act, and Congress began to reconsider the Depression-era law.

In 1999, Congress passed the GLBA, also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act. Among its provisions was the creation of bank holding companies that could perform multiple functions, including:

- Commercial Banking. Accepting deposits and making loans.

- Securities Underwriting. Helping companies with an initial public offering or bond issuance.

- Insurance. Selling and underwriting insurance policies.

- Merchant Banking. Holding equity in companies for the purpose of resale.

The passage of the act created benefits for both banks and their customers. Banks gained the opportunity to serve more of their customers’ needs, consequently increasing revenue per relationship. Consumers and businesses also benefitted from a comprehensive relationship that brought all their financial needs under one roof.

Fewer Banks with More Power After the GLBA

The GLBA ushered in an era of consolidation and financial integration where banks were able to undertake new mergers with previously unrelated financial companies. Some banks bought or merged with insurance firms and brokerage houses – creating conglomerates that remain today.

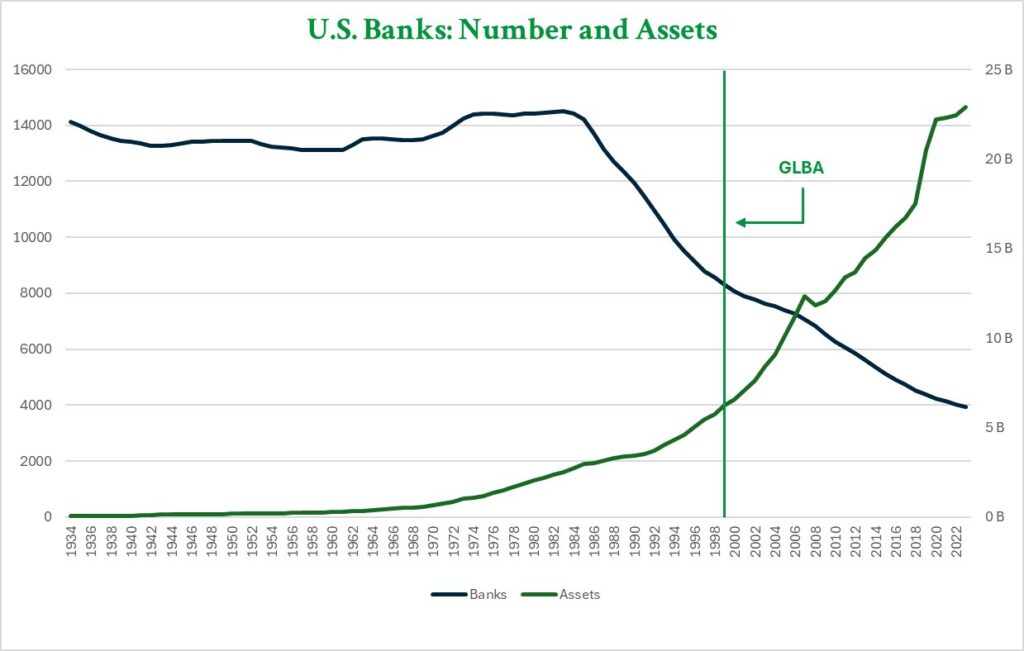

Consolidation led to a drastic decline in the number of banks operating in the United States. In fact, the number of FDIC-member banks fell by more than 50% from 8,582 to 3,928 between 1999 and 2024.

While the number of banks decreased, the value of the banking industry continued to climb. The chart below shows that the total value of assets owned by banks has steadily risen throughout U.S. history, and it continued to climb following the GLBA.

Consolidation coupled with rising assets created the megabanks that dominate the U.S. market today. These institutions are so large and interconnected that the possibility of their failure is a threat to the entire global economy – earning them the name “Too Big to Fail.”

Is Bank Consolidation a Positive Outcome for Business?

The legacy of the GLBA and the system it created is still hotly debated today. On one hand, consolidation offers unmatched convenience for business. On the other, fewer banks means less competition – which can drive deposit rates down, fees up, and hinder personalized service.

Whether the convenience of “one-stop shop” financial institutions outweighs the risks of consolidation remains a key question for regulators and businesses alike. The challenge for cash managers after the GLBA is to leverage the benefits of integrated financial services without jeopardizing the safety or returns of their company’s cash reserves.

Follow ADM for More Banking History and News

Whether you are looking back at history or looking forward to the newest innovations in banking, our company has the information you need. We publish weekly articles that discuss historical perspectives and modern developments in banking, interest rates, and business cash management. Follow us on LinkedIn and subscribe to our mailing list to be alerted when we publish new information.

If your company needs a simpler way to achieve access to full government insurance for cash reserves alongside nationally competitive returns, reach out to a member of our team today. Our deposit management solutions provide access to unlimited FDIC / NCUA insurance, competitive yields, and simple management with a single account.

Key Components of a Business Escrow Agreement

An effective escrow agreement reduces transactional risk by clearly defining the roles and responsibilities of each party.

The One Account Advantage for Business Cash Management

Fragmented cash management creates unnecessary complexity, but a consolidated platform can fundamentally reshape your results.

Q4 Banking Trends: Strong Net Income, Rising Deposits, Lower Unrealized Losses

American banks reported strong net income and lower unrealized losses alongside higher loan balances and deposit levels in Q4 2025.